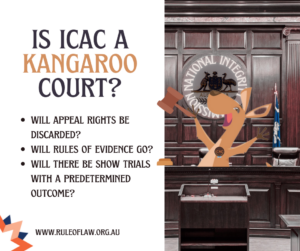

Scott Morrison is right: ICAC is just a kangaroo court

Chris Merritt 6 May 2022

Published in the Australian Newspaper

The nation owes Stephen Rushton a vote of thanks. As one of the three ICAC commissioners in NSW, Rushton’s argument that his organisation is not a kangaroo court should finally ensure this question receives proper scrutiny.

If he is right, we have nothing to fear if the next federal government establishes a national integrity commission based on the NSW model. In those circumstances, Scott Morrison’s concerns about ICAC would be baseless.

But what if Rushton is wrong? That would mean that Morrison, almost alone among public figures, has had the fortitude to call a spade a spade.

In order to test the commissioner’s assertion it is necessary to compare the key structural elements of the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption to the known characteristics of a kangaroo court.

Here is the bottom line: ICAC is a perfect example of a kangaroo court. That is not an insult. It is merely a fact.

Rushton told a committee of the NSW parliament this week that “buffoons” had repeatedly described ICAC as a kangaroo court and this was deeply offensive, misleading and untrue.

In his view, referring to the commission in this way had the capacity to undermine public confidence in the institution and there were vast differences between the functions of the commission and a court.

So how does this stack up?

The Oxford English Dictionary definition is that a kangaroo court should not be an official court — which is in line with Rushton’s point that there are vast differences between a court and the functions of ICAC.

The second feature is that kangaroo courts pursue people without “good evidence” when they are regarded as guilty.

From the US comes this contribution from Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute: a kangaroo court is a “mock court or legal proceeding” in which “some or all of the accused’s due process rights are ignored and the outcome appears to be predetermined”.

ICAC is a mock court. While not part of the justice system, it adopts the outward appearance and formalities of a court and imposes penalties that can last a lifetime – public declarations of corruption whose merits cannot be tested on appeal.

It therefore punishes those it regards as corrupt and deprives them of rights that Cornell Law School would describe as due process. Because there is no merits review, those affected by errors in public findings have limited options.

Cornell’s requirement for predetermined outcomes is not just present but an inevitable outcome of the way the ICAC Act requires the commission to conduct public hearings.

Before it can conduct such a hearing it is required by section 31 of the ICAC Act to decide that it would be in the public interest.

And in making that determination, section 31(2)(a) requires the commission to consider “the benefit of exposing to the public and making it aware of corrupt conduct”.

So before ICAC can validly subject anyone to a public hearing it is required by law to consider whether corruption will be exposed.

Unless the commission decides, before hearing one word of testimony at a public hearing, that corruption is indeed present it would be unable to consider whether there is a benefit in exposing that corruption to the public.

The cart is before the horse. First it decides that corruption is present. Then it decides to hold a public hearing.

Rushton and the other commissioners are not to blame for this. It is a feature of the NSW model. This is why ICAC’s public hearings are vulnerable to the charge that they are mere performances to generate publicity.

It also explains why the NSW Bar Association, in 2015, told an independent inquiry that ICAC’s public hearings “sometimes seem like show trials”.

How could it be otherwise? Questions are asked at public hearings that have already been asked and answered at secret compulsory examinations.

This was made painfully obvious in 2020 when Gladys Berejiklian, the former NSW premier, drew attention to the fact that she was being asked at a public hearing about matters that had already been covered at a private hearing.

At one point Berejiklian reminded counsel assisting, Scott Robertson, that “you brought that matter to my attention during the private hearing” and later still “well, not to my specific recollection, but you brought that to my recollection recently during the private hearing”.

Stephen Rushton, who has worked for ICAC for almost five years, is understandably upset that the commission is not held in universal high regard. The reality, however, is Morrison is right. ICAC is a kangaroo court. It fits the definition precisely.

If public confidence in the commission is suffering it is due to the fact that the NSW government of Dominic Perrottet has sat on its hands while the community has increasingly seen the true nature of this organisation.

Morrison has based his view on legal reality and wants nothing to do with the NSW model. Resorting to abuse, of the kind used this week by Rushton in the NSW parliament, is unseemly and changes nothing.

The onus in this debate is on federal Labor. Which parts of the kangaroo court would form part of its national integrity commission? Will appeal rights be discarded? Will the rules of evidence go? And will there be show trials with predetermined outcomes?