When the United Nations Human Rights Committee found breaches of human rights had taken place in NSW, it asked the federal government to prevent a recurrence.

Those breaches relate to the flawed legal infrastructure surrounding the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption – particularly the failure to permit an appeal on the merits against ICAC’s findings.

These problems, while initially a state responsibility, have now become a responsibility of the federal government.

This is because the Commonwealth, not NSW, signed up to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, subjected Australia to the jurisdiction of the Human Rights Committee, and agreed to provide a remedy when breaches are identified anywhere within Australia.

The inability to run a merits appeal meant businessman Charif Kazal was deprived of the one mechanism that had a real chance of restoring his reputation after it had been trashed by ICAC.

At law, Kazal is an innocent man. When independent prosecutors examined ICAC’s case against him, they refused to charge him with anything.

But the real problem is that Kazal is not alone.

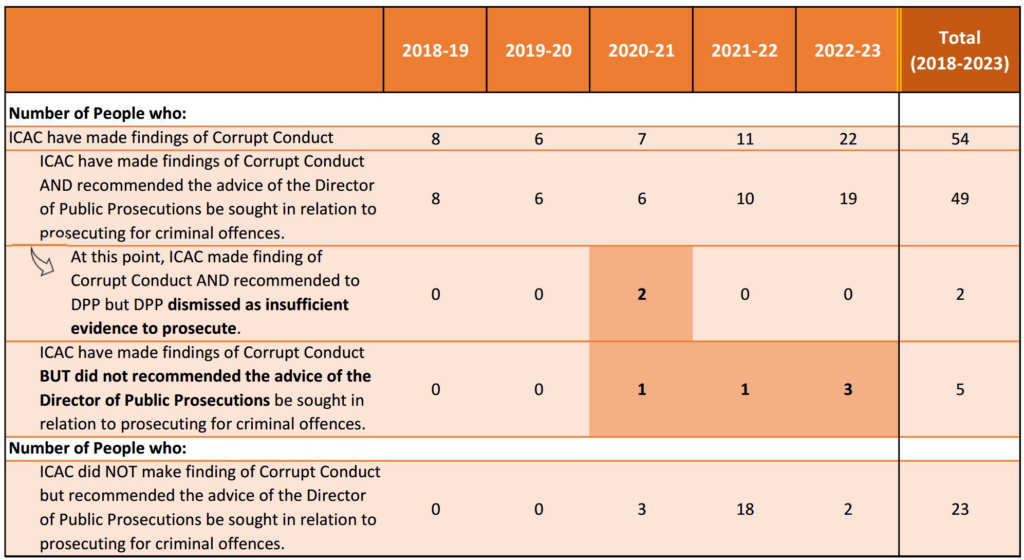

Research by the Rule of Law Institute has found seven other innocent people who are in the same position.

They have been declared corrupt by ICAC and have no way of challenging the merits of those accusations in a court.

Click here to see the Report.

These people have either never been referred to the Director of Public Prosecutions by ICAC, or have been told by the DPP there is insufficient evidence to justify prosecuting them for anything.

Yet according to ICAC they are all corrupt.

They include former NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian who was found corrupt by ICAC but was denied an opportunity to test the merits of this accusation in a court governed by the rules of evidence.

Berejiklian, like Kazal, is limited to a narrowly based judicial review which is restricted to questions of law.

This is the same limitation that the United Nations committee found to be a breach of Australia’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Three of the seven people found corrupt by ICAC in 2020-21 fall into this category: innocent but denied access to the normal courts where they could test the merits of ICAC’s reputation-killing assertions.

Prosecutors told two of these people that ICAC had assembled insufficient evidence to justify charging them with anything. The third person was not even referred to the DPP for prosecution after ICAC’s adverse finding.

These figures, which are based on data published by ICAC itself, do not include the case of former union leader John Maitland who spent almost two years in prison for a crime he did not commit after ICAC said he was corrupt.

Maitland’s conviction was overturned on appeal and in December last year he was acquitted of wrongdoing at a retrial.

After Kazal’s victory in the UN Human Rights Committee, Maitland wrote to federal Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus pointing out that ICAC’s public hearings had destroyed “my reputation, my financial standing but also my family and my life”.

“I have been through the legal system and have been proven not guilty of any wrongdoing yet I am still corrupt according to ICAC and I cannot claim damages.”

Maitland urged Dreyfus to call on the NSW and other state governments to take note of the UN committee’s decision in the Kazal case and support changes that would embrace that decision and limit or extinguish the power of ICAC and similar bodies.

Maitland was stripped of his Order of Australia after ICAC’s adverse finding and the legal costs associated with overturning his conviction meant he and his wife had lost everything, including their family home.

Jumping the gun

Jacqueline Gleeson and Jayne Jagot deserve to be regarded as authors of one of the High Court’s most important and farsighted dissents.

Their disagreement with the rest of the High Court rates just a brief mention in the November 28 judgment in the NZYQ immigration detention case.

But in the light of the political and legal upheaval caused by this case it is worth considering what might have happened if the approach favoured by Gleeson and Jagot had prevailed.

On November 8, they were the only judges who thought it was a bad idea to publish orders freeing one man, known only as NZYQ, from indefinite immigration detention without accompanying those orders with the court’s all-important reasons.

The decision of the majority to publish orders in this case on November 8, while delaying the reasons until November 28, effectively invited speculation and guesswork. And that is what happened.

For 20 days it was impossible to be certain about the central principle – or ratio decidendi – of the case.

The ratio of any judicial decision is the chain of reasoning that supports the ultimate decision. It is to be found in the judges’ reasons, not in their orders.

So without the ratio, there could be no legal certainty about the scope of the principles that underpinned the court’s orders freeing NZYQ.

Yet it was during this period of uncertainty that the government released 147 other foreigners from indefinite detention. They include murderers, rapists and pedophiles.

This explains why there is now debate about whether the government jumped the gun by releasing people based on the court’s orders instead of waiting to see if the ratio required it to free others.

There are two lessons here: A more cautious government would have protected itself from criticism by waiting until the reasons were available. A more cautious High Court would have adopted the approach of Gleeson and Jagot.